Darjeeling beyond tourism: Parimal Bhattacharya’s ethno-memoir — GetBengal story

In social analysis, there is a term that connects data with temporal memory, known as ethnography. By bringing together people’s history, their context, and experiences, a narrative is created. This narrative is mainly analytical, observed neutrally as an outsider. At least in Western sociology (and as reflected in the famous dialogue from the film Agantuk), the tradition of “field notes” has always given importance to this approach. That is why, when Professor M.N. Srinivas introduced his landmark work, “The Village Remembered”, to Indian sociology, it created a new direction in the field.

In that work, through the imagined history of the village Rampura, the plan was to understand the spatial picture of caste. The writing thus became a unique combination of “seeing with one’s own eyes” and “understanding through that act of seeing.” Taking this tradition further, another sociologist, Arvind Das, wrote the biography of his own village, Changel.

It is also a history of place, and of the self. When such material comes into the hands of a literary writer, it too becomes a kind of “temporal-spatial” history. But in this case, the character and the narrator move forward together, with the story itself taking the central place. We see this, for example, in Shankha Ghosh’s Supariboner Sari or Shohorpother Dhulo, where the temporal history is revealed through the autobiographical elements, seen through the eyes of a refugee family’s son.

In Hangras, we saw how Subhash Mukhopadhyay combined his political autobiography with literary narration. In other words, when an academic looks through the telescope, the weight lies more on the urge to understand a scene, a person, or society. But when a writer gently lowers that telescope and looks on a little absentmindedly, their own hand also becomes part of the picture. Why, then, does the discussion of a single book bring in references to so many other writings?

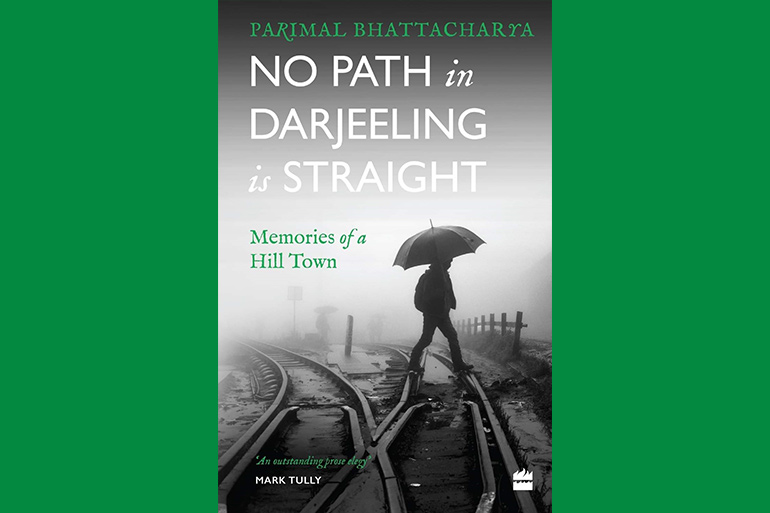

The reason is simple. In his book Darjeeling, author Parimal Bhattacharya brings together both the telescope in hand and the hand of the telescope. This work is one of the rare recent examples of memoir-ethnography in Bengali literature. Even after more than fifteen years since its first publication in 2009, it remains significant.

Through that magical telescope, he gazes at Darjeeling—the beloved destination of the average Bengali—and at times, lowering the telescope, he gently takes the reader by the hand toward “another Darjeeling.” This other Darjeeling is not the tourist’s version of “Five Point” or “Seven Point,” nor the Keventers cafe, nor the dreamy Observatory Hill of the film Kanchenjungha. Bit by bit, he shifts his telescope away from the crowd. At times, the lens of that telescope turns into the magnifying glass of research, as the professor of literature takes up an archival responsibility—writing the history of how Darjeeling was built, of British planning, and of the hard labor of local workers.

Also read : The Darjeeling Mail was once run by bullocks

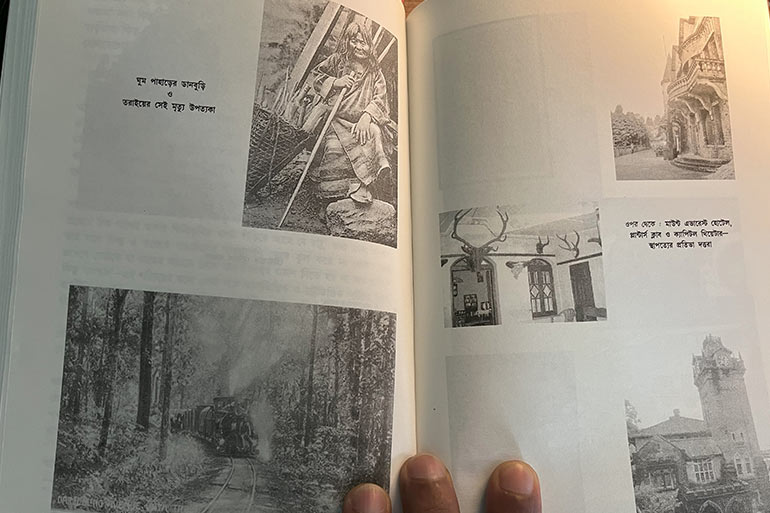

Various patterns emerge from the harsh, slanting lives and everyday struggles of the Lepcha, Gorkha, and Tibetan people, from the cries of water in the mountainous terrain, and from the endless descriptions of complex characters and events. Within these narratives, the author himself is also present. With a gentle smile, he looks at his grandfather’s attitude toward the British and English literature, while a young professor of English—an outsider, almost melancholic—slowly begins to belong to Darjeeling. Mist gathers on the lens of the telescope, and in the dim light of the mountains, blurred through the glass, a narrative is born. Parimal Bhattacharya’s Darjeeling—a narrative of memory, society, and history.

The book consists of five main chapters and two supplementary ones. The introduction itself may also be read as a distinct chapter, where the author acknowledges with gratitude the regional newspapers of Darjeeling and the periodical Baromas. This gratitude has a context—Ashok Sen, associated with Baromas, was at that time, towards the end of the Left Front era, seeking a broader circle beyond partisan politics. Thus, the year 2007, when this writing begins, assumes particular significance.

Although this ethno-memoir has only one central character, the road of Darjeeling. Locally called Chorabato, it winds and bends, climbing and descending around the mountains. When the young professor of “Kosai Khanar Bhore” shifts homes and, in the chapter “Salamanderland”, begins to trace the spatial meanings of Kurseong and Rungit through the Lepcha language, the movement of the book ceases to be that of an outsider. From then on, he keeps asking Darjeeling, through a haze of tender mist, again and again: “O Queen of the Hills, whose are you?”

Through this question, he also reminds us of a certain colonial design. Following that design, the Bengali gaze has long framed Darjeeling as a “British discovery.” Yet, with the deeper lens of his telescope, he reveals the winding trail between 1835 and 1905—a trail of an alternative history, of chorabato. Along that trail appears Hemraj Chhetri, a zoological researcher in search of one of the rarest creatures: the Himalayan salamander.

In other words, against the grain of the colonial plan of “development,” he sets the history of lives and of a vanishing creature. He writes down the histories of bodily labor and survival at the turn of the twentieth century—the stories of khidmatgars and “vistewallas,” of their toil and their lives. That life also includes the local youth—the lives remembered each year on Darjeeling’s Martyrs’ Day, July 27.

And just when he brings us there, the author leads us along another pakdandi—a side-trail. There we meet Benson. He, too, is a professor, but he is searching for the light of Jorethang. A light in whose pursuit, with vodka poured into the gut, an entire town drifts sorrowfully towards the fatal grasp of AIDS. The very people to whom letters were once written are gone. In search of the “spy” character of Kanchenjunga, he halts before a forgotten graveyard.

Hidden within this recurring act of returning lies an intimate political question: “Shailarani, whose are you?”

The author does not attempt to provide any definitive answer. Instead, he leaves the question in the hands of the telescope. At the outset, he breaks apart the apparent typecasts of the Bengali gentleman. He writes about the concealed disdain hidden behind such belief, exposing the assumption: “Hill people are simple (meaning foolish here).” Into this discourse, he brings his student Newton—whose home in Jhalapahar becomes the entry point to a long-lost Limbu dictionary, and with it, the politics of identity. This leads us deeper into another winding chorabato (hidden path) of the Gorkhaland movement’s long and complex politics.

Once again, in the seemingly calm days of the 1990s, he invokes local poetry—the verses of a melancholy young man. In the lines of Yumita Rai’s poetry, we encounter:

“...নবগঠিত কাউন্সিল ছুঁড়ে দিল কিছু রুটির টুকরো

নিতান্তই অল্প, যদিও সেটাও বন্ধ হয়ে গেল। তারপর

শোষণ… বেকারত্ব… অবসাদ

এবং, অবধারিত যা।

বিশের চৌকাঠ পেরিয়ে আমি মাদকাসক্ত হলাম।”

(“…The newly formed council tossed us a few crumbs of bread—

meagre as it was, even that came to an end.

Then came exploitation… unemployment… despair—

and, what was inevitable.

Crossing the threshold of my twenties,

I became an addict.”)

To view this politics of identity in a binary: the demand for a separate state set against the question of dignity within the same state. Beyond the logic of development, the author brings in his most significant passage here.

“The British taught us the ways of measuring forests, rivers, and people respectively in cubic feet, cubic seconds, and IQ… The real problem is that the refugees of development often do not speak in the language of economics; instead, they say—Give us back our geography! Give us back our language! Leave us the sacred valley of our ancestors’ spirits…” (Page 140, Darjeeling)

This book keeps gazing into the faces of the people of the valley, while its central question lingers: ‘Queen of the Hills, who do you belong to?’

Through that wondrous lens of enchantment, this book allows us to connect our own intimate melancholy with the melancholy of Darjeeling. It touches the politics of our sorrow—where the solitude of the self and the solitude of the valley intertwine in this ethno-memoir.

Note:

Translated by Sabana Yasmin

To read the original Bengali article, click here: